The Washington Post

By Sean Yom

Monkey Cage Analysis

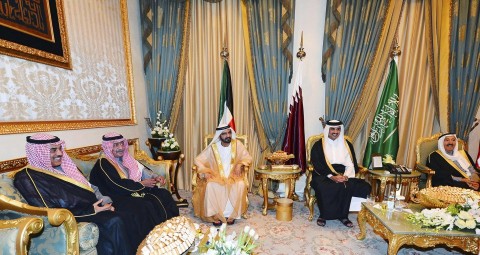

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) leaders meet at a summit in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on Nov. 16, 2014. (Saudi Press Agency via Reuters)

The term “community” connotes positive outcomes in global affairs. An international community opposes war crimes and supports humanitarian goals; epistemic communities share information and ideas for common causes like climate change; security communities, such as NATO, spread peace and deter aggression among members; and democratic communities like the European Union innovate “best practices” of governance and defend human rights.

But dictators have communities, too.

Authoritarian states under duress can band together, share ideas, circulate strategies and stick by a collective identity in ways that mimic democracies. This is true in the post-Arab Spring Middle East. Since 2011-2012, there has been unprecedented convergence in policy across the eight Arab monarchies — Morocco, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman and the UAE. These countries suffered far less turmoil than republics like Egypt and Tunisia, but their citizens were no less demanding of political change.

In response, these eight autocracies communicated, consulted and conjured the beginnings of a monarchical community, one predicated on a unique “pan-royal” identity that shared a singular fate. As near-absolutist dynasties under siege by revolutionary forces, they had to respond collectively. Those responses have been felt in both domestic and foreign policy, from new forms of repression, deeper sectarianism, the evisceration of mass media and potential GCC expansion.

During the Arab Spring, calls for isqaat (downfall) rumbled through the streets of many countries, but the kingdoms also saw popular calls for malakiyyah destouriyyah (constitutional monarchy). A loaded phrase, it reminded royal absolutists that — unlike other ruling kingships around the world, which had since fallen or transitioned to democracy — the Arab dynasties still clung to power based upon an antiquated notion of legitimacy. They felt besieged by history in a way that republican dictators could not understand. After all, autocracies exist everywhere in the world, but outside the Middle East, only tiny Swaziland and Brunei remain ruling monarchies.

[This piece is also featured in POMEPS Studies 20 From Mobilization to Counter-Revolution – read the full collection here]

That existential fear did not make royal palaces turn inward. On the contrary, they reached out to one another, circulating old and new ideas as never before. Their collective identity was not about Arabness, but rather royalness — the belief that as an endangered species, they shared an immutable commonality that could not be denied and must be protected by new firewalls to keep out the contagious spread of unrest and revolution. By February 2011, when the Mubarak dictatorship collapsed in Egypt, observers saw a marked rise in communication between the monarchies. This included not only direct lines between kings but also lower-level exchanges among cabinet ministers, senior princes and private emissaries.

For instance, frequent summits assembled foreign ministers representing just these eight kingdoms. Notably, the monarchies did not use the Arab League, the nominal organization charged with coordinating regional affairs, to come closer together. They did so on their own, using not just diplomatic channels but also informal familial networks forged in past decades by royal intermarriage, friendships and business ventures. Many of these exchanges — such as the “royal-only” ministerial meetings — persisted well beyond the 2011-2012 period.

The fruits of such communing included new policy initiatives to help preserve the beleaguered citadel of Arab royalism. In February 2011, Saudi Arabia led the push to turn the GCC, an otherwise ineffectual security alliance, into a bigger “monarchies club” by including Morocco and Jordan as new members. In pure realist terms, this made little sense to the oil-rich Gulf, given the weakness of the Moroccan and Jordanian militaries, as well as their poorer economies and need for greater aid. Being strategic allies alone also cannot explain this. After all, neighboring pro-Saudi Yemen had long lobbied to join, but even at the height of its uprising in 2011, no Gulf monarchies suggesting giving the Yemeni regime membership to save it.

Consider the inverted geographic logic of this. Rather than adding another Gulf country to the Gulf Cooperation Council, royal leaders fancied the inclusion of two non-Gulf countries. The common denominator? Royalism.

Ultimately, the GCC did not expand, but because of a startling reason: some of the smaller Gulf kingdoms, such as Kuwait, feared the spread of popular uprisings from Morocco and Jordan to the Gulf. In any case, the rich Gulf kingdoms provided Jordan and Morocco all the benefits of membership without its formality, investing many billions of dollars through aid and deals since 2011.

Another manifestation of royal communalism unfolded within domestic policy with the practice of “cross-policing,” in which royal governments smothered domestic critics of other Arab monarchies. Since 2012, there have been dozens of cases of cross-policing. Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood official Zaki Bani Irsheid was arrested and jailed for a year by his home country after posting criticism of the UAE on Facebook. In Kuwait, parliamentarians who censured the policies of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the Emirates have been detained and imprisoned. In Bahrain, critics of Saudi Arabia are treated little better than enemies of the Khalifa monarchy.

This cross-policing possible is made possible by a little-known agreement reached in November 2012 called the Joint Security Agreement, which nominally covered the Gulf kingdoms but to which Morocco and Jordan also assented. The JSA calls for signatories to suppress any citizen who endangers the domestic affairs of other kingdoms, making it markedly unsafe for anyone living under these monarchies to criticize any other Arab monarchy. Further, many royal governments have also passed new “anti-terror” statutes and laws since 2012 that mirror one another in key ways. They extend the reach of censorship onto cyberspace and use deliberately vague language to give state authorities extreme leeway to prosecute chosen targets.