US News

HIGH above the sprawling concrete landscape of ships, trucks and docks of the Tangier Med Port are the words “God, Nation, King,” laid out in massive white Arabic letters on a mountainside. As the sun sets on the port, the letters become illuminated, glowing and shedding bright white light on the surrounding hillsides. On those hillsides, beneath the glow, are boys curled up asleep, with trash bags as their only covering.

“There is no place for us to sleep among a lot of other things,” says Ayoub, a small 13-year-old boy on a particularly windy day last April. Ayoub — and other children interviewed for this article — refused to share their last names, saying they live in fear of the police. Ayoub says he’s been living at the port for 15 days with very little money or food. He has no phone or way of contacting his family.

He is one of thousands of Moroccan children attempting to migrate to Spain each year, and one of the millions of child migrants worldwide, a figure that reached 30 million in 2017.Countries That Accept the Most MigrantsView All 12 Slides

Though Moroccan children have long attempted — and often succeeded — at illegally migrating, the number has grown in recent years. The number of minors looking to migrate just through the small Spanish enclave of Ceuta to Spain has risen from 800 in 2017 to more than 3,300 in 2018, according to the Spanish news agency Europa Press, citing official data. Nearly 100% of these minors are Moroccan, according to the data.

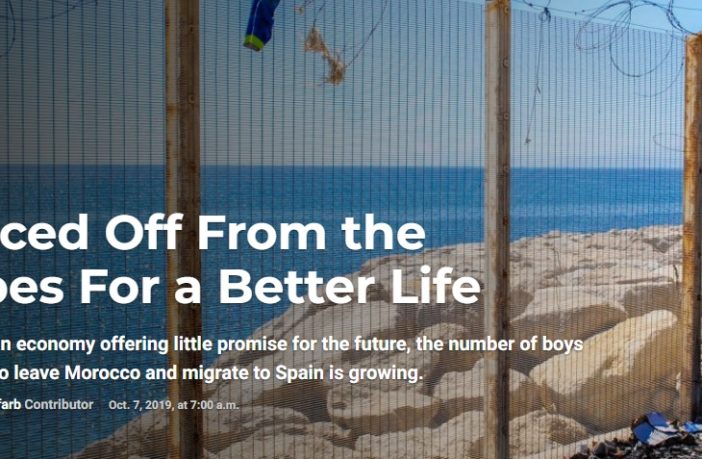

Ayoub came to Tangier from a village near the city of Settat in central Morocco with his friends: 15-year-old Youssef, 15-year-old Wadie, and another boy named Ayoub, 14. The group of boys are getting some rest before the days or weeks of travel ahead of them. Separating these children from Spain is the Strait of Gibraltar, a distance of 9 miles at its narrowest point. Some kids attempt to scale the fences around the port, sometimes injuring themselves. Others stow under the hoods of trucks next to running engines, hoping to be smuggled across.

Moroccan children are not the only ones making this journey; of the child migrants that arrived in Spain in 2017, others came from Syria, Algeria, Ivory Coast and Guinea. But it is the dire economic landscape in Morocco that is driving this current surge. The International Labor Organization estimates that Morocco, as of 2018, has a youth unemployment rate of nearly 22%, compared to the estimated global youth unemployment rate of about 12.7%.

A Childhood Cut Short

So far, Ayoub and his friends have failed to cross despite countless attempts. “We haven’t been able to see our family for quite a while,” Ayoub says. After several weeks of living on the street, they show their hands, covered in dirt and cuts. They appear to be the hands of men, not boys.

Just recently, the Arab Barometer’s 2019 Morocco Report (a research project produced by the BBC) found that 70% of Moroccans under 30 consider emigrating from their homeland. The reasons why the boys are seeking to migrate are common.

“Because we can’t benefit from an education nor find a job,” says the 14-year old Ayoub. “Our parents are tired and if we keep at this pace they will eventually grow old and end up with nothing and there is nothing we can do to help them.”

While undocumented migration into the EU has dropped, a survey by Frontex (the European Border and Coast Guard Agency) last year shows the number of undocumented crossings into Spain, mainly from Morocco, doubled in 2018 to 57,000, according to the BBC.

Meanwhile, in February, Morocco reinstated the compulsory military draft, a move that is expected to draw an estimated 10,000 men between the ages of 19 and 25 into the service this year alone. The goal of the draft, according to Abdellatif Loudiyi, Morocco’s minister-delegate for national defense, is to improve social cohesion by weaving the men into the country’s social circles, according to the state-run news agency Moroccan News Agency.

But the draft and Spain’s deportation law are attempts to control, rather than solve, the issue of young, unemployed Moroccans, according to Mercedes G. Jiménez Álvarez, director of International Cooperation Programmes at the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID) through the Spanish Embassy in Rabat, Morocco.

“People don’t believe there can be a future for work,” says Jiménez, also a consultant for UNICEF, during a recent interview in Tangier. “There is no hope.”

Boys walk in Tangier in hopes of finding a way onto a ferry to Spain.(KATE BREWER)

Desperation Trumps Risk and Danger

Such desperation is palpable at the Tangier Med Port. Despite the risk and danger of migrating out of Morocco, these young Moroccans are so intent on leaving they are willing to leave their families and sometimes risk their lives to change their futures.

The recent increase in migration from Africa to Spain has led to a crackdown on migration in Morocco. These crackdowns, which can include arrest and deportation, are being attributed to the pressure — and incentives — Morocco receives from Europe. In September of 2018, the EU gave Morocco $275 million in aid to help with basic services and job creation. Nongovernmental organizations attempt to help as well, but those efforts come with expiration dates. In September 2019, a USAID-funded project called Favorable Opportunities to Reinforce Self-Advancement For Today’s Youth (FORSATY) was terminated after seven years.

Though crackdowns usually target sub-Saharan migrants, they have also affected Moroccan migrants. A 22-year-old Moroccan woman was shot and killed by the Moroccan Royal Navy after boarding a boat crossing illegally into Spain a year ago, and children report abuse from both Moroccan and Spanish police.

“We are scared of the security who control the port,” says Ayoub’s friend Wadie. “They take our clothes away, hit us.” Though only 15, his taller, leaner figure makes him appear much older.

Ilyas, a 12-year-old boy trying to migrate through Ceuta, has had similar experiences. “Yes,” he says, “they (the Spanish police) hit us with batons.” He says encounters with the Moroccan police have been equally abusive.

The Spanish consulate in Tangier did not return requests for comment.[

MORE: Morocco’s Doctors, Medical Students Protest Privatization ]

Searching for Solutions

Despite the lofty goals some NGOs preach, Jiménez asserts that rather than help Moroccan minors find jobs at home, the relief efforts have failed.

“That is the contradiction of the programs preventing migration,” she adds. “It is a fallacy. How are you going to prevent migration? Europe comes to pay you to not move.”

Jiménez, the Spanish official in Rabat, believes the responsibility for solving the problem of youth migration is twofold.

“It is a responsibility on Morocco’s side,” she says. “They have to take responsibility of their children. They are their kids. On the other hand, Europe has to have a diligent treatment of these children, because they are theirs too. It is a shared responsibility. And until now there is a shared failure, too.”

Lauren Goldfarb spent months in Morocco on a SIT Study Abroad program, and produced this story in association with The Round Earth Media program of the International Women’s Media Foundation. Amine Erraadi and Soukaina Messou, who studied at the Connect Institute in Agadir, Morocco, contributed reporting.

Photos by Kate Brewer and audio by Giulia Villanueva.